متحف الزهراء

نيتو سوبيجانو

قرطبة | اسبانيا

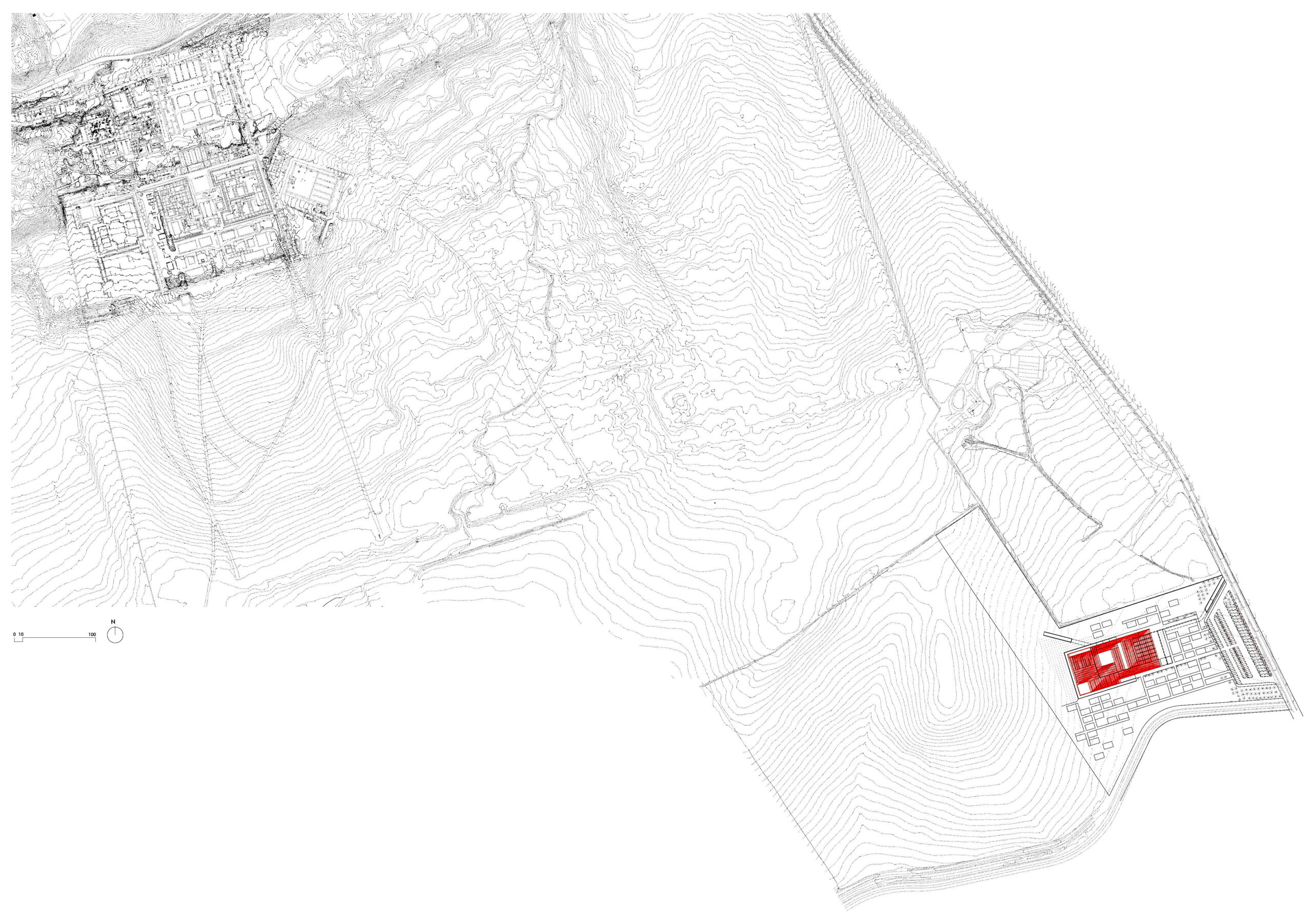

The Romantic image of ruins, so often rejected for being nostalgic and anachronistic, is nonetheless able to convey not only the evocative power of buildings from the past but also the destructive strength of time and nature. In this -construction, destruction-resides, perhaps, the fascination that archaeological remains possess not only as reminders of the disappeared buildings, but also as triggers for the mental reconstruction of other, future architectures. At least this is how we understood the situation when we visited the archaeological precinct of Madinat al-Zahra for the first time. The remains of the old Hispano-Muslim city suggested a dialogue with those who, a thousand years earlier, had conceived and built it, as well as with the patient work of archaeologists and with the surrounding agrarian landscape, to which the geometry of the ruins gave an unexpected abstract quality.

The terrain of the archaeological site for the museum, however, stirred up mixed feelings. On the one hand, the yearning for a remote past yet to be discovered pervaded the landscape stretching all the way to the mountain ranges of Córdoba. On the other hand, the disorderly growth of new constructions loomed uncomfortably over the old city. Our first reaction upon arriving at the site determined our proposal from the very outset: we should not build in that landscape. In such a vast expanse of land, still waiting to be excavated, we decided to act as an archaeologist would: not building a new structure, but unearthing it below ground, as if the passage of time had concealed it until now.

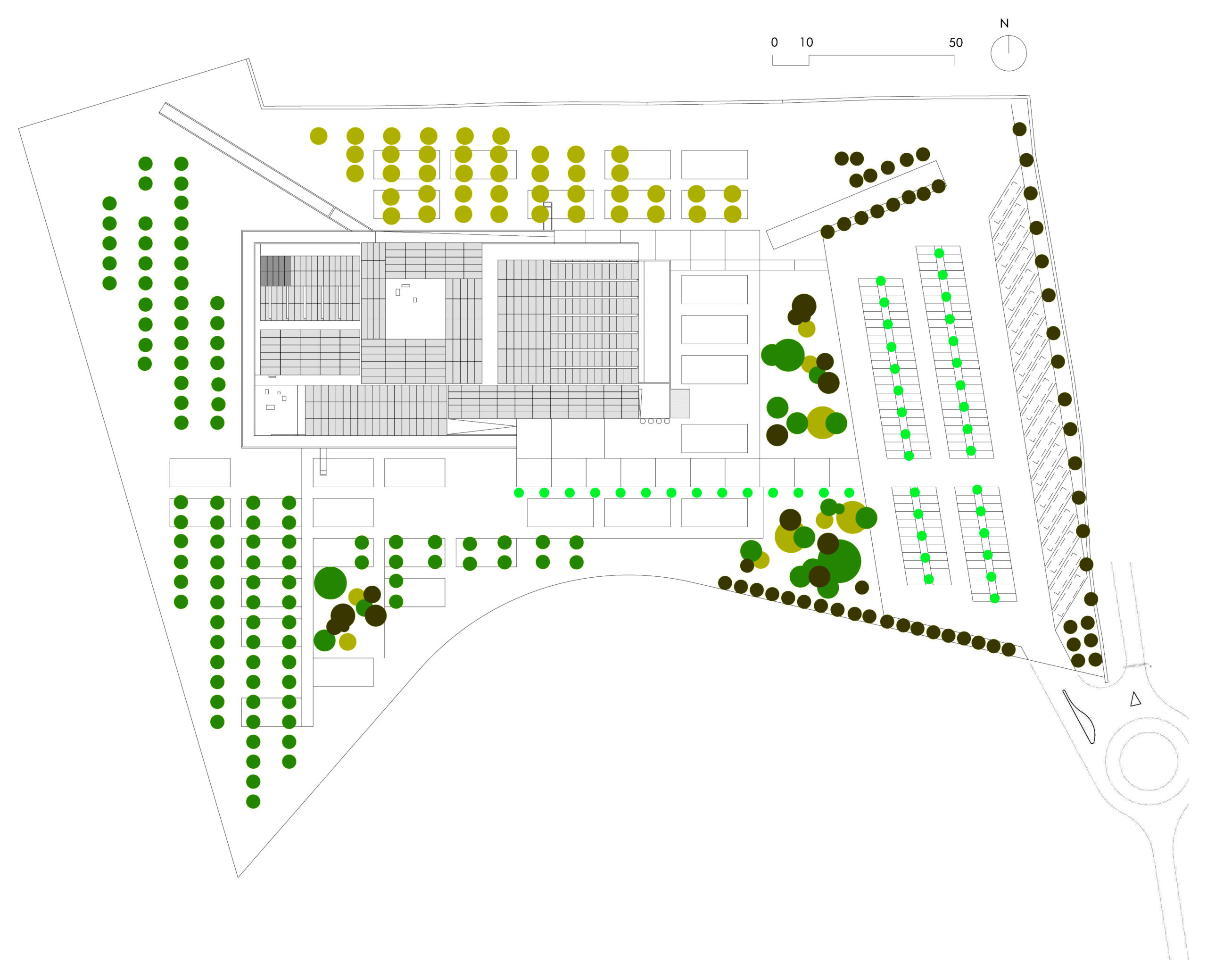

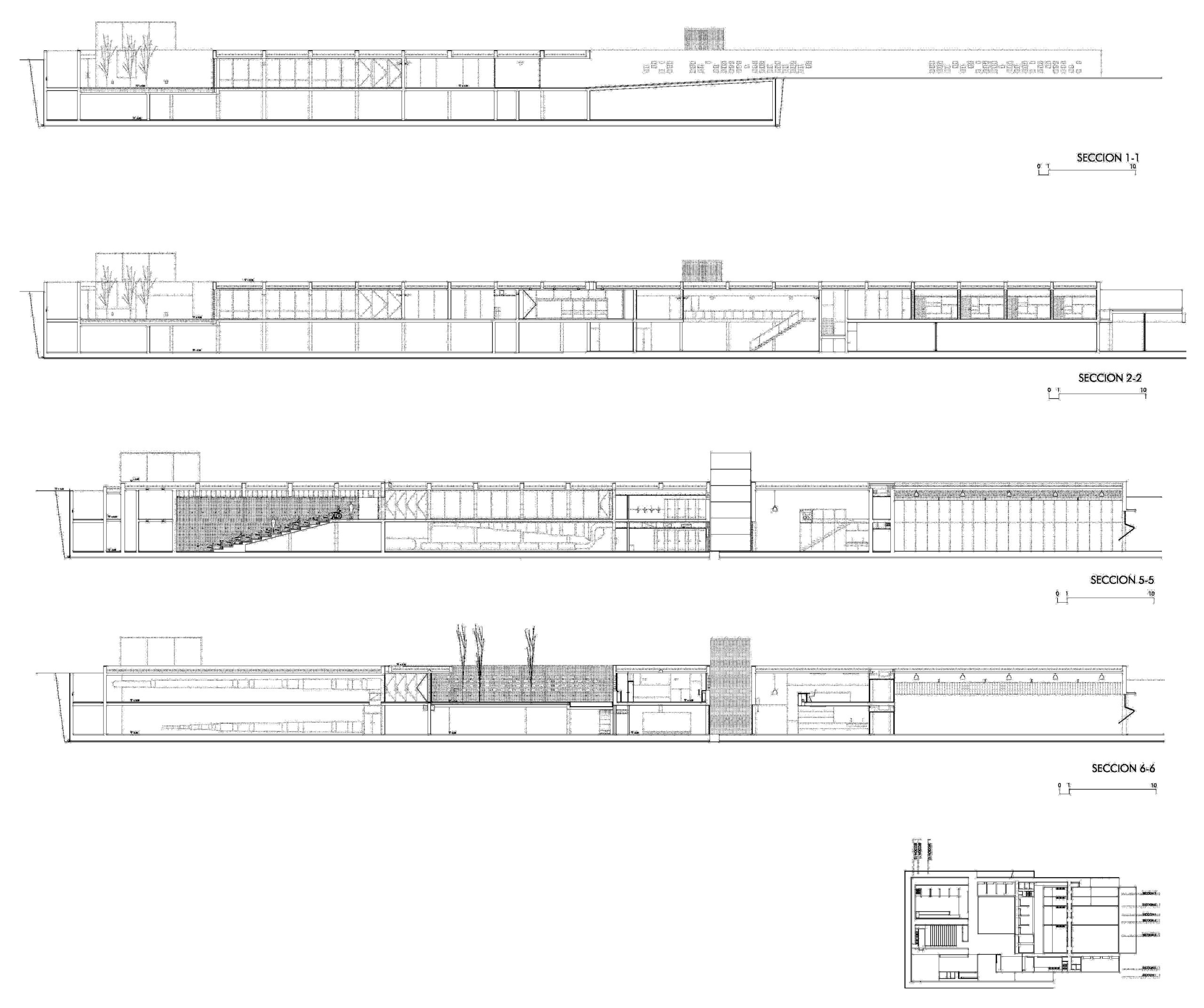

“We established a two-dimensional orthogonal grid, a point of origin and reference height. We marked the rectangular boxes from which the terrain excavation must start and eliminated the series of layers in strata of a standard thickness. This patient task yielded hopeful results, revealing the floor plan of a building whose walls were used to configure the museum, auditorium, workshops, and storage space. We then defined the walls, raised a first level, and covered them. Upon discovering pavements of old courtyards and corridors we renovated them and turned them into key elements of the new project. Finally, we delimited the context of our intervention, building a perimeter enclosure: a precinct that will protect the remains found.”

This text, excerpted from our competition statement, is perhaps the one that best conveys the original idea -the metaphor of an excavation- so that our task ultimately consisted of revealing and unearthing, as archaeologists still do, the architectures hidden below ground. In this way, the project unveils the floor plan of an underground museum, which articulates its halls around a sequence of solid and void spaces, covered areas and courtyards that guide visitors along their itinerary. The main lobby leads to a large courtyard with a square floor plan that, like a cloister, organizes around it the main public spaces: assembly hall, cafeteria, store, library, and exhibition halls. A deep, elongated courtyard articulates the private-use areas: administration, conservation workshops, and research zones. A final courtyard is the expansion of the museum exhibition areas toward the exterior. The storage areas, conceived as large skylit rooms, blend with the public and exhibition spaces. The conception of the project allows for further expansion, making it possible to add pavilions as if they were new excavations. The new museum establishes almost imperceptibly a permanent dialogue with the architecture and the landscape of the old Arab medina. The double-square floor plan of the museum is homothetic to that of the city; the gardens evoke the abandoned geometry of an excavation; and the concrete walls and cor-ten steel roofs reflect the white and red colors of the stuccoed walls of the Caliphal city. Light, shadow, texture, and matter evoke the palpable richness of the archaeological ruins. The architecture thus becomes a spatial and formal expression of its constructive support, a connection so often forgotten these days. Every time we visited the site, the new walls we were raising recalled those that had been destroyed and were now being unearthed by archaeologists just a few meters away, in an inverse process -construction, destruction- which seemed to encapsulate the whole sense of the project. The Madinat al-Zahra Museum has emerged silently in the landscape, as if it had been discovered underground, just as it will keep on happening with the old white city of the Umayyad Caliphs over the course of the years.

Location Córdoba, Spain

Client Government of Andalucía

Architects Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos, Fuensanta Nieto, Enrique Sobejano

Program Archaeological museum and research centre

Total floor area 7.293 m2

Project architect Miguel Ubarrechena

Project team Carlos Ballesteros, Pedro Quero, Juan Carlos Redondo

Site supervision Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos, Fuensanta Nieto, Enrique Sobejano, Miguel Mesas Izquierdo

Structural engineer N.B.35, S.L.

Mechanical engineer Geasyt, S.A.

Museographic project Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos / Frade Arquitectos, S.L.

Photographs Aurofoto, S.L. (models), Roland Halbe, Fernando Alda, Rafael Tena

Competition 1999

Design 2002

Completion 2009